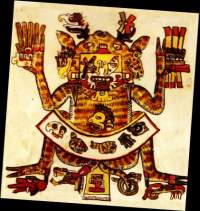

Mictlancihuatl (Mictecacihuatl; Lady of Mictlan) Wife of Mictlantecuhtli, lord of the underworld, she was a goddess of death

Mictlancihuatl (Mictecacihuatl; Lady of Mictlan) Wife of Mictlantecuhtli, lord of the underworld, she was a goddess of death

Sabtu, 25 Oktober 2008

Aztec Gods-Mictlancihuatl

Mictlancihuatl (Mictecacihuatl; Lady of Mictlan) Wife of Mictlantecuhtli, lord of the underworld, she was a goddess of death

Mictlancihuatl (Mictecacihuatl; Lady of Mictlan) Wife of Mictlantecuhtli, lord of the underworld, she was a goddess of death

Aztec Gods-Mictlantecuhtli

Mictlantecuhtli (Lord of Mictlan) God of death and the underworld (Mictlan, or “place of the dead”), he is identified with gloom and darkness. He is frequently represented as a skeleton with bloody spots. He is married to Mictlancihuatl. Quetzalcoatl fought with Mictlantecuhtli to retrieve the bones of human beings of the previous era and create them again in the present era, the fifth sun. This battle symbolized the constant interaction and duality between life and death.

Mictlantecuhtli (Lord of Mictlan) God of death and the underworld (Mictlan, or “place of the dead”), he is identified with gloom and darkness. He is frequently represented as a skeleton with bloody spots. He is married to Mictlancihuatl. Quetzalcoatl fought with Mictlantecuhtli to retrieve the bones of human beings of the previous era and create them again in the present era, the fifth sun. This battle symbolized the constant interaction and duality between life and death.Aztec Gods-Mayahuel

Mayahuel (Goddess of Maguey) As the maguey deity, she is associated with pulque. Mayahuel isdepicted sometimes with attributes of the water goddess, including fertility and fecundity. She is most often represented as emerging from a flowering maguey plant. According to a myth, she was killed by the tzitzimime, and when Quetzalcoatl buried her bones, the first maguey sprouted. In other accounts, she is mentioned as “the woman of four hundred breasts,” probably a reference to the sweet milky aguamiel (sap) of the maguey, which, when fermented, produces pulque.

Mayahuel (Goddess of Maguey) As the maguey deity, she is associated with pulque. Mayahuel isdepicted sometimes with attributes of the water goddess, including fertility and fecundity. She is most often represented as emerging from a flowering maguey plant. According to a myth, she was killed by the tzitzimime, and when Quetzalcoatl buried her bones, the first maguey sprouted. In other accounts, she is mentioned as “the woman of four hundred breasts,” probably a reference to the sweet milky aguamiel (sap) of the maguey, which, when fermented, produces pulque.Aztec Gods-Macuilxochitl

Macuilxochitl (Five Flower) He is the principal god of the Ahuiateteo and the patron god of the palace folk as well as of games and gambling, especially the patolli game. In addition, Macuilxochitl is the deity of the flowers and excessive pleasures. He punishes people by inflicting hemorrhoids and diseases of the genitals. He is closely associated and often overlapping with Xochipilli, the Flower Prince.

Macuilxochitl (Five Flower) He is the principal god of the Ahuiateteo and the patron god of the palace folk as well as of games and gambling, especially the patolli game. In addition, Macuilxochitl is the deity of the flowers and excessive pleasures. He punishes people by inflicting hemorrhoids and diseases of the genitals. He is closely associated and often overlapping with Xochipilli, the Flower Prince.Aztec Gods-Itztlacoliuhqui-Ixquimilli

Itztlacoliuhqui-Ixquimilli (Curl Obsidian Knife) He is the deity of castigation, blindness, and stoning and also the god of frost, snow, and coldness.

Itztlacoliuhqui-Ixquimilli (Curl Obsidian Knife) He is the deity of castigation, blindness, and stoning and also the god of frost, snow, and coldness.Aztec Gods-Itzpapalotl

Itzpapalotl (Obsidian Butterfly) Earth goddess of war and sacrifice by obsidian knife, she is identified with the bat and the tzitzimime (star “demons” that devoured people during the solar eclipses). Itzpapalotl is a fearsome deity.

Itzpapalotl (Obsidian Butterfly) Earth goddess of war and sacrifice by obsidian knife, she is identified with the bat and the tzitzimime (star “demons” that devoured people during the solar eclipses). Itzpapalotl is a fearsome deity.Aztec Gods-Ilamatecuhtli

(Cihuacoatl, Citlalicue, Quilaztli;

(Cihuacoatl, Citlalicue, Quilaztli;Aged Woman) Goddess of Earth, death, and the Milky Way, Ilamatecuhtli wears a skirt with dangling shells known as a star skirt and is depicted with a fleshless mouth. She was worshipped in a temple called Tlillan (darkness). Her festival was Tititl, during which a female slave who impersonated her was sacrificed.

Sabtu, 26 Juli 2008

Huitzilopochtli

(Hummingbird of the Left, Hummingbird of the South) Supreme and patron deity of the Aztec, god of sun, fire, and war, he is the Blue Tezcatlipoca. He wears a blue-green hummingbird headdress and carries the xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent that is the weapon he uses to fight his enemies. He frequently is represented bearing on his back the anecuyotl, the head of a fantastic animal. He led the Mexica during part of their pilgrimage from Aztlan to the promise land of the Valley of Mexico and determined the place of the foundation of Tenochtitlan, their capital city. He was worshipped in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan and was honored with massive human sacrifices throughout the year. The god Painal, an avatar of Huitzilopochtli, was associated with warfare and the ball game as a metaphor of war.

Aztec God - Huehueteotl

(Old God) God of the hearth and the household and lord of fire. He is represented as an old figure with his legs crossed and his hands resting on the knees. Often he has some features of Tlaloc, expressing a link between the two deities. He holds in his head a huge brazier that was used for burning incense or even to produce fire.

Selasa, 01 Juli 2008

Aztec God - Huehuecoyotl

Huehuecoyotl (Old Coyote) He is the god of dance, music, and carnality, and the patron deity of feather workers.

Huehuecoyotl (Old Coyote) He is the god of dance, music, and carnality, and the patron deity of feather workers.Aztec God - Cihuateteo

(Women Gods) One of two groups of supernaturals who accompany the Sun on its passage from east to west, the Cihuateteo are female warriors, or women who have died in childbirth . They haunt the crossroads at night, can cause seizures and insanity in people, and are known to steal children. They also seduce men and cause them to commit adultery and other sexual transgressions.

Organization of the Aztec Pantheon

In the official Aztec religion, 144 Nahuatl names corresponded to the gods. Of these names, 66 percent belong to deities considered masculine, and 34 percent, to deities of feminine gender. According to historian Rafael Tena, the important gods of the Aztec pantheon can be identified through three different, complementary methods: 1) the analysis of the functions of the gods, 2) the frequency whereupon they received an official cult, and 3) the presence of their respective temples within the ceremonial enclosure of Tenochtitlan the Handbook of Middle American Indians (1971:

In the official Aztec religion, 144 Nahuatl names corresponded to the gods. Of these names, 66 percent belong to deities considered masculine, and 34 percent, to deities of feminine gender. According to historian Rafael Tena, the important gods of the Aztec pantheon can be identified through three different, complementary methods: 1) the analysis of the functions of the gods, 2) the frequency whereupon they received an official cult, and 3) the presence of their respective temples within the ceremonial enclosure of Tenochtitlan the Handbook of Middle American Indians (1971:395–446) proposed distributing the Aztec gods into three groups consisting of 17 gods who ruled over similar functions and powers.

1. Creative and provident gods

- Ometeotl, the Dual Divinity or the Divine Pair: supreme deity

- Tezcatlipoca, Smoking Mirror: creative, omnipotent god

- Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent: creative and beneficial god

- Xiuhtecuhtli, Lord of the Year or Lord of the Turquoise: god of the fire

- Yacatecuhtli, Lord at the Vanguard: god of merchants and travelers

2. Gods of agricultural and human fertility and of pleasure

- Tlaloc, “the one that is made of earth”: god of waters

- Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl, Wind-Feathered Serpent: god of wind

- Xochipilli, the Flower Prince: god of the fertilizing sun and of joy

- Xipe Totec, Our Flayed Lord: god of the vegetation that must perish but is reborn

- Cinteotl, God of the Maize

- Metztli, Moon: deity of the Moon

- Teteoinnan, Mother of the Gods: universal mother goddess

3. Gods that conserve the energy of the world but require the nutriments of war and human sacrifices to replenish their power

- Tonatiuh, “the one that is illuminating”: god of the Sun

- Huitzilopochtli, Hummingbird of the South: solar god of war, the tutelary god of the Mexica

- Mixcoatl, Cloud Serpent: god of the Milky Way

- Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, Lord of the Dawn: god of the planet Venus

- Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Place of Dead: god of the underworld

THE GODS IN RITUALS

Each celebration of the xiuhpohualli (the solar year) had a corresponding god or gods worshipped in ritual.

These celebrations include the following:

Atlcahualo, or Cuahuitlehua: Tlaloque Tlacaxipehualiztli: Xipe Totec and Huitzilopochtli, Tlaloque Tozoztontli, or Xochimanaloya: Tlaloque, Coatlicue Huey Tozoztli: Cinteotl, Chicomecoatl, Chalchiuhtlicue, Tlaloque Toxcatl: Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli Etzalcualiztli: Tlaloque and Chalchiuhtlicue Tecuilhuitontli: Huixtocihuatl, Xochipilli Huey Tecuilhuitl: Xilonen and Cihuacoatl Tlaxochimaco, or Miccailhuitontli: Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli, Mictlantecuhtli Xocotlhuetzi, or Huey Miccailhuitl: Xiuhtecuhtli-Otontecuhtli, Yacatecuhtli, Mictlantecuhtli Ochpaniztli: Teteoinnan-Toci, Tlazolteotl, Coatlicue, Cinteotl and Chicomecoatl Teotleco: Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli, Huehueteotl, Yacatecuhtli Tepeilhuitl, or Huey Pachtli: Tlaloc, Tlaloque, Tepictoton, Centozontotochtin, pulque gods, major mountains Quecholli: Mixcoatl, Camaxtle, Huitzilopochtli, Coatlicue Panquetzaliztli: Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, Painal, Yacatecuhtli Atemoztli: Tlaloque, Tepictoton mountains Tititl: Ilamatecuhtli, Cihuacoatl, Tonantzin Yacatecuhtli Izcalli, or Huauhquiltamalcualiztli: Xiuhtechtli, Tlaloc, Chalchiuhtlicue Other celebrations of the xiuhpohualli were the Pillahuano (Xiuhtecuhtli), Atamalcualiztli (Cinteotl), and Toxiuhmolpilia, or New Fire ceremony (Xiuhtecuhtli, Huitzilopochtli).

Celebrations of the tonalpohualli (ritual lunar calendar) also worshipped particular gods. They include the following:

Nahui ollin, “4 Movement”: Tonatiuh

Chicome-xochitl, “7 Flower”: Chicomexochitl

and Xochiquetzal

Ce-mazatl, “1 Deer”: Cihuapipiltin

Ome-tochtli, “2 Rabbit”: Ometochtli and

Izquitecatl

Ce-acatl, “1 Cane”: Quetzalcoatl

Ce-miquiztli, “1 Death”: Tezcatlipoca

Ce-quiahuitl, “1 Rain”: Cihuapipiltin

Ome-acatl, “2 Cane”: Omeacatl

Ce-tecpatl, “1 Knife”: Huitzilopochtli, Camaxtle

Ce-ozomatli, “1 Monkey”: Cihuapipiltin

Ce-itzcuintli, “1 Dog”: Xiuhtecuhtli

Ce-atl, “1 Water”: Chalchiuhtlicue

Ce-calli, “1 House”: Cihuapipiltin

Ce-cuauhtli, “1 Eagle”: Cihuapipiltin

The most important Aztec gods based on their frequency in Aztec rituals were therefore Tlaloc (Tlaloque) and Chalchiuhtlicue, Xiuhtecuhtli-Huehueteotl-Otontecuhtli, Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, Cinteotl and Chicomecoatl-Xilonen, Mixcoatl, Yacatecuhtli, Ometochtli, Xipe Totec, To- natiuh, Cihuapipiltin, Teteoinnan-Toci, Tlazolteotl, Ilamatecuhtli-Cihuacoatl, Coatlicue, Quetzalcoatl, Mictlantecuhtli, Painal, Omeacatl, Huixtocihuatl, Xochipilli-Chicomexochitl, and Xochiquetzal.

The Nature of the Aztec Gods

The Aztec gods were anthropomorphic and related through the bonds of kinship. The numerous gods of the Aztec pantheon had complex hierarchies. Although the gods were immortal, and as such would exist into eternity, this did not prevent them from dying or returning to life an infinite number of times.

The gods had superhuman powers and resided in the different levels of heaven and the underworld, as well as inhabiting specific places on Earth. They could be called upon to manifest themselves instantaneously at many different sites. When the Aztec gods were summoned they could visit human beings in diverse ways, often appearing in dreams or through fantastic visions or disguised as nahualtin (singular, nahualli), or animal embodiments. These beings were generally zoomorphic and important to rituals and the auguries of Aztec divination. Nahua can be found in Aztec iconography depicted in the codices and chronicles with characteristics that allowed for their identification.

Although the gods were benevolent and provident in their relationship with humankind, they could also be frightful, arbitrary, and maleficent. They presided over special scopes of nature or aspects of human culture and could be adopted as protectors by an ethnic or socioeconomic group.

The Origin of the Aztec Gods

The Aztec religion was polytheistic (belief in many gods) and was therefore composed of a multitude of gods and goddesses. Every town, neighborhood, and family had a corresponding deity. Additionally, every plant, and human traits. The Aztec gods embodied fundamental Aztec principles such as the concept of duality, the predilection for multiplicity (polytheism) over individuality (monotheism), and the important connection between the gods, humans, and the natural environment.

Although the Aztec religion was indeed very complex and can be described as polytheistic, there is also a certain tendency toward a theoretical monotheism (belief in a primordial single god). Aztec poets and philosophers, for example, bestowed many epithets on the primordial god Ometeotl, the Lord of Duality:

Ipalnemoani, “the giver of life”; Tloque Nahuaque, “the one that is everywhere” or “the ever present”;

Moyocoyani, “the one that acts by itself with absolute freedom” or “the one who invents himself.” Although the creator Ometeotl was also known as Tezcatlipoca, Tonatiuh, and Xiuhteuctli-Huehueteotl, it was understood that they all represented preeminent personifications of the supreme deity. The supreme deity was eternal but somewhat remote from the world and from human beings; therefore, other gods were sent to mediate in the affairs of men and women. These gods exhibited benevolent powers in many senses, but they were also subject to the limitations and imperfections of the earthly realm. They could be moved by a whim or through passion, be hurt or maimed, and could suffer debilitation and be subject to death.

The Mexica considered the supreme deity Ometeotl to be both the father (Ometecuhtli) and mother (Omecihuatl) of the other gods. Both fundamental beings were called Tonacatecuhtli and Tonacacihuatl, the Lord and Lady of Our Sustenance, deities that nourished humanity.

The Aztec religion was inclined to syncretism rather than proselytism. When the Aztec conquered other towns they did not impose their own gods onto the conquered nations but rather incorporated the gods of the peoples they conquered.

Therefore we find a variety of gods who serve as patrons of sorcerers, nomadic hunters, soldiers, agriculturists, fishermen, as well as gods from particular regions, inhabiting the tropical forests, the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico, the Pacific Ocean, and the central plateau

Kamis, 26 Juni 2008

The Mythical Foundation of Tenochtitlan

The Aztec began as a tribe of people known as the Mexica or Mexitin, their name derived from their lord, Mexi. They left Chicomoztoc (the Seven Caves) located in the mythical land of Aztlan in 193 C.E. in search of their promised land. The migration was long and hard, lasting hundreds of years, and many settlements were founded en route. They were Huitzilopochtli, who would communicate to his people and advise them along their course via the priests, who were mediators between the earthly and the celestial realms.

The Aztec began as a tribe of people known as the Mexica or Mexitin, their name derived from their lord, Mexi. They left Chicomoztoc (the Seven Caves) located in the mythical land of Aztlan in 193 C.E. in search of their promised land. The migration was long and hard, lasting hundreds of years, and many settlements were founded en route. They were Huitzilopochtli, who would communicate to his people and advise them along their course via the priests, who were mediators between the earthly and the celestial realms.When the Aztec finally reached the Valley of Mexico in the 13th century, they knew that they were close to their promised land, but Huitzilopochtli warned them of hardships to be encountered in this already-settled land. He urged them to prepare themselves accordingly. This land was none other than the area once controlled by the great city of Teotihuacan and later by Tula, which had been settled for hundreds of years prior to the arrival of the Aztec to that region. There were still many settlements in the area that were remnants of those grand civilizations, and so following the advice of Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec fortified themselves and prepared for battle in Chapultepec. However, the Aztec and their patron god had other adversaries to contend with, namely Huitzilopochtli’s nephew Copil, who was out to avenge his mother, Huitzilopochtli’s sister Malinalxochitl. Huitzilopochtli had ordered that Malinalxochitl, who was once part of the caravan in search for the promised land, be left behind, for she had developed wicked and evil practices of witchcraft and could contaminate the rest of the caravan. Accordingly, Malinalxochitl and her flock were abandoned, left alone to fend for themselves.

Copil could not bear his mother’s betrayal by his uncle, so he set out to search for Huitzilopochtli. He soon learned of Huitzilopochtli’s arrival at Chapultepec in the Valley of Mexico. Once in the valley, Copil gained support from the surrounding towns by telling them of the atrocious and tyrannical ways of the Aztec, thus joining forces and gaining the military support necessary to overcome the Aztec. Certain of the Aztec defeat, Copil went to the hill called Tepetzinco, or Place of the Small Hill, to view the massacre from a good vantage point. However, Huitzilopochtli could not be outwitted, as he was well aware of his nephew’s plans. He therefore instructed his people to go to Tepetzinco, where hot springs ran at the base of the hill. Huitzilopochtli demanded that they slay Copil, pull out his heart, and bring it to him.

The priest, Cuauhtlequetzqui, carrying an image of Huitzilopochtli, led the delegation to Tepetzinco and proceeded to do as Huitzilopochtli instructed. Once the heart of Copil was presented to Huitzilopochtli, he instructed the priest to throw the heart into the center of the lake. The place where Copil’s heart landed was called Tlacocomolco. Despite this defeat, the peoples from the region still wanted the Aztec to be ousted from their territory and so began to wage war against them. The enemies, namely the Chalca, continued to surround Chapultepec Hill and attacked the Aztec. They succeeded in their attack and even managed to capture the Aztec leader, Huitzilihuitl. The survivors, who included women, children, and the elderly, sought asylum in a deserted town named Atlacuihuayan (Tacubaya). The Chalca did not find it necessary to follow the survivors, as they were few and disenfranchised.

After replenishing themselves, the defeated Aztecs rebuilt their forces, and upon Huitzilopochtli’s request for them to be strong and proud, they went to their enemies at Colhuacan to ask for a place in which their wives and children could stay and live in peace. After much deliberation with his council, the king of Colhuacan granted the Aztec a site by the name of Tizapan, a most undesirable site, where snakes, reptiles, and other beasts resided. However, the Aztec took the offer and made that land theirs, taming the harsh environment and making do with what was given to them.

Later, the king of Colhuacan had his messengers report on the status of Tizapan. He was amazed to learn that the Aztec had cultivated the land, built a temple to Huitzilopochtli, and made the snakes and local reptiles a part of their diet. Impressed with the news he received from his messengers, the king granted the requests made by the Aztec that they be allowed to trade in Colhuacan and that they be able to intermarry with the people of Colhuacan. This was not the promised land of the Aztec, however, and Huitzilopochtli requested, via the priests, that they leave this land in search for the true Aztec capital, adding that their departure must be a violent departure, not a peaceful one. Huitzilopochtli ordered his people to ask the king of Colhuacan, named Achitometl, for his daughter, so that she might serve Huitzilopochtli and become a goddess, to be called the Woman of Discord. The Aztec did as they were told by their god.

King Achitometl agreed to this honor, and after the pageantry that followed this transaction between the tribes, the young woman was taken to Tizapan. Once in Tizapan, she was proclaimed Tonantzin (Our Mother) by the Aztec and then sacrificed in the name of Huitzilopochtli. As was customary and part of Aztec ritual practices, after the young woman was sacrificed, her skin was flayed. Her flayed skin was worn by a “principal youth” who sat next to the Aztec deity. From that time on, she was both Huitzilopochtli’s mother and bride and was worshipped by the Aztec.

King Achitometl was summoned and, not knowing that his daughter had been killed, accepted the invitation and attended the ceremony with other dignitaries of his town, bringing precious gifts in honor of his daughter, the new Aztec goddess, and the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli. When King Achitometl entered the dark temple, he commenced his offerings and other ceremonial rights. As he drew closer to the figures, with a torch light in his hand, he was able to discern what was before him, the youth wearing the flayed skin of his daughter and sitting next to their deity. Disgusted and filled with fright, the king left the temple and called on his people to bring an end to the Aztec.

The Aztec fought vigorously, and although they were pushed into the water by the opposition, they managed to flee to Iztapalapa. The Aztec were in a state of desolation. Huitzilopochtli tried to comfort his people who had suffered so much in search of their promised land. They were not far from it, so the Aztec continued moving from town to town, seeking refuge where they could.

One day as they roamed the waters, they saw signs that had been prophesied by the Aztec priests. One was a beautiful, white bald cypress (ahuehuetl), and from the base of the tree a spring flowed. This spring was surrounded by all white willows. All around the water were white reeds and rushes, and white frogs emerged, as well as white snakes and fish. The priests recognized all these signs as predicted by their god and rejoiced for they had found their promised land.

Soon after, Huitzilopochtli came to the priest named Cuauhtlequetzqui and told him Copil’s heart, which was thrown into the lake as prescribed by him, had landed on a stone, and from that stone a nopal (prickly pear cactus) sprang. The nopal was so grand and magnificent that an eagle perched there daily, feeding from its plentiful fruits and enjoying the sun. It would be surrounded by beautiful and colorful feathers from the birds that the eagle fed on.

The priest relayed this message to the people, who responded with joy and enthusiasm. Once more they went to the spring where they had seen the wonderful revelations of their god but were surprised to find two streams instead of one, and instead of white, one stream was red and the other was blue. Seeing all this as good omens, the Aztec continued their search for the eagle perched on a nopal, which they soon beheld. The people bowed their heads to this sight in all humbleness, and the eagle did the same in turn. They had finally reached their promised land, and here they built Tenochtitlan.

On the Mexican flag today is an eagle proudly standing on a nopal, which grows from a stone. This symbolism speaks to the Aztec myth and to the Aztec’s perseverance and spiritual belief system. Indeed, Tenochtitlan went on to be the capital of the Aztec Empire.

In pre-Hispanic imagery of this myth, the fruit that grows from the cactus is represented as human hearts, and in the eagle’s beak is an atl tlachinolli, a symbol of fire and water that could have been mistaken for a snake by the colonists, for this is what appears in the eagle’s beak on the modern-day flag. Today, Aztecs Art is sometimes used for Interior Design all around the world.

The Birth of Huitzilopochtli

Unlike most pre-Hispanic myths, which share many of the same characteristics, the myth of Huitzilopochtli is uniquely Aztec. Huitzilopochtli is therefore considered to be the cult god or the patron god of the Aztec. As a solar deity, Huitzilopochtli is closely related to and overlaps with Tonatiuh. Huitzilopochtli’s mother was Coatlicue, or She of the Serpent Skirt. Coatlicue, known for her devout nature and virtuous qualities, was at Mt. Coatepec one day, sweeping and tending to her penance, when she discovered a bundle of feathers on the ground. She decided to save them and placed them in her bosom. Without her realizing, the feathers impregnated her. Coyolxauhqui, Coatlicue’s daughter, and her 400 brothers, collectively called the Centzon Huitznahua, became enraged when they saw that their mother was pregnant. Prompted by Coyolxauhqui, and in an episode of pure anger and disgrace, they plotted to kill their own mother.

Unlike most pre-Hispanic myths, which share many of the same characteristics, the myth of Huitzilopochtli is uniquely Aztec. Huitzilopochtli is therefore considered to be the cult god or the patron god of the Aztec. As a solar deity, Huitzilopochtli is closely related to and overlaps with Tonatiuh. Huitzilopochtli’s mother was Coatlicue, or She of the Serpent Skirt. Coatlicue, known for her devout nature and virtuous qualities, was at Mt. Coatepec one day, sweeping and tending to her penance, when she discovered a bundle of feathers on the ground. She decided to save them and placed them in her bosom. Without her realizing, the feathers impregnated her. Coyolxauhqui, Coatlicue’s daughter, and her 400 brothers, collectively called the Centzon Huitznahua, became enraged when they saw that their mother was pregnant. Prompted by Coyolxauhqui, and in an episode of pure anger and disgrace, they plotted to kill their own mother.Coatlicue, aware of her children’s plants, was consoled and assured by her unborn son. Then, as Coyolxauhqui and the Centzon Huitznahua reached Coatepec to slay their mother, Coatlicue gave birth to Huitzilopochtli. In a move to save his mother, Huitzilopochtli, who was born fully armed, stabbed and beheaded Coyolxauhqui with his xiuhcoatl, or “turquoise serpent,” a sharp weapon. Her body fell from Coatepec, and broke into pieces at the base of the mountain. He then proceeded to kill his half brothers, murdering nearly all of them with the exception of the few that got away and fled south. It was believed that Huitzilopochtli was the Sun, and the Centzon Huitznahua constituted the stars, disappearing with the rising of the Sun. The Great Temple in the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, served as a monument to this myth. The pyramid’s south side represented Coatepec, the Serpent Mountain, and it was there at the base that a huge round stone of Coyolxauhqui’s dismembered body was excavated. This massive carved stone served as a reminder of Huitzilopochtli’s defeat of his enemies. Incidentally, it was at the Great Temple that many sacrifices took place, as if reenacting the slaying of Coyolxauhqui, for the sacrificed bodies, usually of captives or prisoners, were thrown down from the top of the pyramid, landing on the Coyolxauhqui stone. Like Tonatiuh, Huitzilopochtli required blood and hearts from sacrificed subjects in order to make his track across the heavens and assuring the Sun’s appearance in the east every morning.

The Origin of Pulque

Now that humans had food, a sun, and a moon, they needed something that would bring joy to their lives. The gods gathered and decided that the people of the fifth sun should be able to partake in something that would make them want to rejoice with music and dance. One night, Quetzalcoatl went to the goddess Mayahuel, the goddess of maguey (agave plant), and convinced her to descend to Earth with him.

Once on Earth, they bound themselves into a tree, each taking up a branch. When Mayahuel’s grandmother woke up the next morning, she found that her granddaughter was missing. Enraged, the grandmother summoned the tzitzimime, the demonic female celestial entities, embodied as the stars above, and told them to go find Mayahuel. When they found the tree that was holding both Quetzalcoatl and Mayahuel, the tree split into two, dropping the branches to the ground. Recognizing the branch that hid Mayahuel, the grandmother proceeded to shred it, giving parts to the tzitzimime so that they could eat greedily and consume her. They did not touch Quetzalcoatl’s branch, and once they left, he shape-shifted back to his usual form. In mourning, he proceeded to bury what was left of Mayahuel. It was from this humble grave that the first maguey plants sprang forth, and from the sap of this plant was made the alcoholic beverage pulque. Pulque was used in Aztec rituals and ceremonies, as well as in celebrations and festivals, and is still enjoyed today by contemporary Mexicans.

Sabtu, 14 Juni 2008

The First Human Beings and the Discovery of Maize

The fifth sun needed to be populated, as the people from the previous sun had been exterminated. Quetzalcoatl journeyed into the underworld, known as Mictlan, to retrieve the bones of the dead of the fourth sun from Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Land of the Dead, and his wife Mictlancihuatl. From those bones, Quetzalcoatl would re-create the human beings necessary to inhabit the new world. Mictlantecuhtli agreed to release the bones to Quetzalcoatl under one condition: Quetzalcoatl had to sound a conch shell four times around Mictlan. This seemingly easy task was a trick; the conch that Mictlantecuhtli gave Quetzalcoatl was flawed—it did not have any holes—making it impossible for Quetzalcoatl to sound the conch. Quetzalcoatl, however, could not be fooled, and he ordered worms to burrow holes into the shell. Additionally, he had bees go inside the conch shell in order to produce a loud, resonating sound.

The fifth sun needed to be populated, as the people from the previous sun had been exterminated. Quetzalcoatl journeyed into the underworld, known as Mictlan, to retrieve the bones of the dead of the fourth sun from Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Land of the Dead, and his wife Mictlancihuatl. From those bones, Quetzalcoatl would re-create the human beings necessary to inhabit the new world. Mictlantecuhtli agreed to release the bones to Quetzalcoatl under one condition: Quetzalcoatl had to sound a conch shell four times around Mictlan. This seemingly easy task was a trick; the conch that Mictlantecuhtli gave Quetzalcoatl was flawed—it did not have any holes—making it impossible for Quetzalcoatl to sound the conch. Quetzalcoatl, however, could not be fooled, and he ordered worms to burrow holes into the shell. Additionally, he had bees go inside the conch shell in order to produce a loud, resonating sound.Seeing that Quetzalcoatl had met his condition, Mictlantecuhtli allowed Quetzalcoatl to take the bones, but before long, he had a change of heart. Mictlantecuhtli set a trap, and Quetzalcoatl fell into a deep pit. Being a deity, Quetzalcoatl was able to revive himself and escaped the underworld with the bones, which had broken in the fall.

Upon ascending to Earth from the underworld, Quetzalcoatl went to a place called Tamoanchan to grind the bones with the aid of the goddess Cihuacoatl, also known as the Woman Serpent and patron of fertility. To bring life to the bones, Quetzalcoatl and other deities drew blood from their male members and poured it over the bones. The bones were revived from the blood of the gods, and thus the first human beings of the fifth sun were created. Because the bones were broken on their way from the underworld, humans of the fifth sun are composed of many different sizes. The first human couple created were Cipactonal and Oxomoco.

To feed the people, Quetzalcoatl transformed himself into an ant in order to be able to enter Mt. Tonacatepetl, also known as the Mountain of Sustenance, which contained the food for the new peoples. From the mountain, he gathered the grains of maize, which would become the main food source for the people of the fifth sun. However, in order for a ready supply to be continually available, the god Nanahuatzin was summoned to open up Mt. Tonacatepetl. With the help of the four Tlaloc gods, or gods of rain, Nanahuatzin succeeded in opening up the mountain and spilling the seeds and kernels, which became the food supply for the new people. Tlaloc is thus always associated with crops, as he is the main purveyor of rain and therefore also associated with fertility.

The sun god Tonatiuh and the rain god Tlaloc helped humans produce maize and flowers, which provided life and joy on Earth. Because the gods had volunteered to sacrifice themselves in order to activate the Sun and Moon, they maintained life in the universe. The gods, then, by means of their will, effort, and sacrifice, bestowed life to humans, and for that reason men and women were called macehualtin, “the deserved ones.” Humans, in return, were forced to be thankful to the gods for these benefits and were obligated to sustain the gods with maize and other Earth products. However, due to the dual nature of the Earth, the good things of the world were also threatened by the possibility of droughts and cataclysms that could bring destruction and death. The Aztec ensured the continued benevolence of the gods by appeasing them with continued propitiation rituals and human sacrifice.

Creation of the Fifth Sun in Teotihuacan

According to Mexica and Nahuatl tradition, the gods gathered in the dark at Teotihuacan, to plan the creation of the fifth sun. The arrogant god Tecuciztecatl volunteered himself to be the new Sun and bring light to the Earth. The gods agreed to this and asked Nanahuatzin, a modest god, to accompany the proud Tecuciztecatl.

After doing penance in the two hills erected especially for them, the two gods, dressed in their ritual regalia, were ready to sacrifice themselves by jumping into a ritual bonfire at Teotihuacan. Tecuciztecatl felt fear to jump into the bonfire, so the first god to sacrifice himself was Nanahuatzin, also known as the Proxy One, and who was dressed modestly, showing his humble nature. Bravely, he threw himself into the fire without hesitation. He then rose to the heavens, first appearing in the east as the Sun and a proud new god, now named Tonatiuh. Ashamed, Tecuciztecatl then jumped into the fire, rising to the heavens to become the Moon. However, so as not to usurp the brightness of the Sun, one of the gods threw a rabbit up at the Moon, thus dimming its brightness and forever emblazoning the rabbit’s image on the Moon’s face for future generations to witness. To continue bathing the world with his solar rays, Tonatiuh demanded blood from the other gods in order to move along his course. Upon witnessing the bravery displayed by these two gods, the other gods agreed to sacrifice themselves and embraced death, thereby ensuring the Sun’s radiance and movement across the sky. Quetzalcoatl began to pull the hearts from the gods with a sacrificial blade. Therefore, to ensure the Sun’s movement, subsequent humans had to be sacrificed in order to thank and appease the deity Tonatiuh.

Consequently, Teotihuacan, whose Nahuatl name means “place where they become gods,” is the site of the Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon, commemorating the gods Nanahuatzin, who became the sun god Tonatiuh, and Tecuciztecatl, who became the god of the Moon. The ancient city marks where the fifth sun was created.

The Legend of the Suns

According to Aztec mythology and as evidenced in the Aztec Calendar (Sun Stone), before the present age there were four previous ages, or worlds. Each world had a name that corresponded to the calendar, as well as a deity and a race of people. Each world was also associated with one of the four elements: earth, water, fire, and wind. In addition to sharing the attributes of its corresponding element, the demise of that world would be dictated by its ruling element.

The previous worlds, better known as “suns,” were each created out of destruction. Each sun’s demise was due to a natural catastrophe prompted by a fight between the two conflicting deities, Quetzalcoatl, representing life, fertility, and light, and the Black Tezcatlipoca, representing darkness and war. Each cataclysm was prescribed by the sun’s ruling element and would bring an end to the world and death to all of its inhabitants.

Out of death and destruction, however, a new and better world was born, in which humanity lived in a more perfect stage than that of the previous suns. The four previous ages were the sun of ocelotl (jaguar) or earth, the air or wind sun, the fire sun, and the sun of water. Note that these are the suns of the four elements.

After the destruction of each world, the Black Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl were in charge of recovering the lost cosmic order together, with the winner of the argument of the previous age presiding over the next sun. All four Tezcatlipocas were engaged in the re-creation of the entire world and universe and its inhabitants.

The first sun, the world of the ocelotl or earth, was ruled by the Black Tezcatlipoca and was populated by giants. This sun ended as a result of Quetzalcoatl overpowering and defeating Tezcatlipoca by throwing him into the sea, whereupon Tezcatlipoca emerged as a jaguar. Other deadly jaguars also emerged, devouring the giants that roamed the Earth and thus ending the first sun. As a result of Quetzalcoatl’s victory over Tezcatlipoca, he presided over the second sun, the wind sun. Tezcatlipoca returned to Earth to topple Quetzalcoatl and was victorious, bringing this sun to an end by a hurricane wind. The third sun, the sun of fire rain, was presided over by Tlaloc, the rain god. For the second time, Quetzalcoatl was responsible for ending another world, this one destroyed by fire that rained from the sky. The fourth sun was presided over by Chalchiuhtlicue, Tlaloc’s sister. This sun of water was destroyed by a deluge, in which the resulting flood cleared out everything. As a result, the people of this previous world were turned into fish. After the deluge that ended the fourth world, the present age, the sun of movement, came into existence. The fifth sun will conclude on a day called nahui-ollin (4 Movement), as a result of earthquakes.

Understanding The Underworld

According to the Codex Vaticanus A, the underworld was made up of nine layers, eight of which were underneath the Earth’s surface. The nine layers were the inhabitable Earth, the passage of waters, the entrance to mountains, the hill of obsidian knives, the place of frozen winds, the place where the flags tremble, the place where people are flayed, the place where the hearts of people were devoured, and the place where the dead lie in perpetual darkness. The downward journey into the underworld was taken by the souls of the dead until they reached the ninth level, known as Mictlan Opochcalocan, and where they resided for eternity.

Understanding the The Terrestrial Plane

From Ometeotl the four Tezcatlipocas were born, each identified with a cardinal direction. Of the four, the Black Tezcatlipoca was the god Tezcatlipoca (Smoking Mirror); he was the most venerated and feared. Quetzalcoatl, or the white Tezcatlipoca, was the Black Tezcatlipoca’s polar opposite, for Quetzalcoatl was a benevolent god and was associated with the color white and with the west. However, because of their dual natures, possessing both good and bad qualities, representing black and white, and life and death. Quetzalcoatl and the Black Tezcatlipoca were constantly engaged in a cosmic struggle, a struggle that would result in both the end and the beginning of worlds. The Earth and the universe were thus created from this cosmic struggle and would therefore comprise both benevolence and evil.

The terrestrial plane was thought of in terms of five cardinal directions: the east, north, south, west, and center, or axis mundi. Each direction had a particular god, symbol, and color and often had its own bird, plant, or tree. The east stood for the region of Tlapallan, symbolized with a reed as it was associated with Xipe Totec, the Red Tezcatlipoca, god of vegetation and renewal of nature. The Black Tezcatlipoca could be seen in the north ruling over Mictlampa, the region of the dead, symbolized by flint. The Blue Tezcatlipoca, also known as Huitzilopochtli, the god of the Sun and of war, corresponded to the south, the region of Huitztlampa, signified by the rabbit. The White Tezcatlipoca was commonly identified with the west, called Cihuatlampa, represented by the calli, or house. At the center of the Earth was the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. Tenochtitlan corresponded to the concept of cemanahuac, the idea that the primordial homeland consisted of a tract of land (tlalticpac) surrounded by water. Tenochtitlan also resembled the original Aztec city of Aztlan, which had also been erected on land surrounded by water. Within Tenochtitlan was the ceremonial enclosure of the Great Temple, with two altars of Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc atop .

The two most important celestial bodies were the Sun and the planet Venus, also known as the Morning Star, whose arrival was anticipated with fear. The gods of the Sun and Venus were invariably conceived as masculine, whereas the Moon and the Earth were both masculine and feminine. Humans lived in Tlalticpac, which means “on the Earth.” The Earth, in addition to being on the back of a marine monster, was also thought to be a gigantic toad, whose face formed the entrance to the underworld, and who devoured the dead.

Understanding the Aztec Celestial Plane

The Aztec universe was layered and stratified, and celestially embodied the hierarchical values of the earthly realm. The celestial plane was composed of 13 different levels. It is probable that of these 13 levels, the “inferior skies” (those closer to Earth) were incorporated into the inhabitable Earth. According to the Codex Vaticanus A (Codex Rios) and the Historia de los mexicanos por sus pinturas, the 13 skies from top to bottom were the dwelling of Ometeotl (Omeyocan), the red sky, the yellow sky, the White sky, the sky of ice and rays, the blue-green sky of the wind, the black sky of the dust, the sky of stars of fire and smoke (stars, planets, and comets), the dwelling of Huixtocihuatl (salt or saltwater and birds), the dwelling of Tonatiuh (the Sun and the demonic female entities known as tzitzimime, the dwelling of Citlalicue (Milky Way), the dwelling of Tlaloc (rain) and Metztli (the Moon), and the inhabitable Earth Ometeotl—the Dual Divinity, or Lord of Duality—was the Aztec creator god and engendered both male and female qualities. Ometeotl dwelled in the 13th sky, the highest heaven, known as Omeyocan. From this great vantage point, Ometeotl was able to preside over the entire universe, including the Moon, the Sun, and the stars, all of which inhabited the lower skies.

Jumat, 09 Mei 2008

Aztec God #6 - Coatlicue

Coatlicue, also called as Teteoinan ( "mother all gods") is the Aztec patroness who created stars, moon and Huitzilopochtli, she is also described as the god of the sun and battlefield. It is also called Toci, (grandmother), and Cihuacoatl, (" snake woman"), the patroness of woman who die during childbirth.

"Coatlicue" is nahuatl for "a person skirt made from snakes." It is covered by phrases "The Earth Goddess Mother who brings forth celestial beings" "patroness of fiery fire and fertility", "patroness of life, death and reborn" and "Mother of the Southern Stars" .

She is described as a woman with a skirt of coiling serpents and necklace created from the heart of men, hands and skulls. Her limbs are shown with long claws for grave digging and her large breasts are shown as suspended due to frequent nursing.

Almost each depiction of the goddess represent a deadly side, because the Earth and loving mother, is the insatiated beast that eat all living things. It is represented as a mother who devours.

According to myth, she was impregnated by magic when he was still a maiden by a feather ball that drop on her when she was cleaning a temple. She then mother of Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl. In a fit of anger, all four hundred of her children were told by Coyolxauhqui (her daughter) to behead her. The Huitzilopochtli then emerged from Coatlicue's womb into spontaneous full maturity and bring forth a epic battle, in where he killed almost of his sisters and brothers, including beheading Coyolxauhqui and lay its head in the sky as the Moon. In other variation on this myth, Huitzilopochtli is born from the feather ball incident and born in time to rescue his beloved mother from danger.

A huge sculpture called as Coatlicue Stone was found by astronomer Antonio de Leon y Gama in August 1790 after a program of urban renewal. Half year later, the team found the huge stone Aztec sun. De Leon y Gama finding was the first archaeological work on pre-Columbian Mexico.

Aztec God #5 - Cihuacoatl

Cihuacoatl ( "snake woman", so Chihucoatl, Ciucoatl) was one of the patroness for motherhood and fertility.

Cihuacoatl is related to midwives, and associated with sweatbaths as a practice medium for midwives. She and Quetzalcoatl create the human race nowadays from the bones of the previous races, and then mixed it with Quetzalcoatl blood. She gave birth to Mixcoatl, who was left behind at a crossroads. It was told that she often returns to cry for his long lost son, but what she find is only a sacrificial knife.

Even if she always described as a young woman that looked more like Xochiquetzal, it is frequently presented as a fierce skull face-old woman. Delivery by a woman is sometimes compared to a battle and women who died in labor were honored similar to fallen warriors.

Aztec God #4 - Chicomecoatl

Chicomecoatl ( "Seven Serpent", is also a name of Aztec day) is a goddess of physical nourishment especially corn and the fertility goddess.

Each September, there would be a sacrifice of decapitated maiden. her blood would be spread on the statue of Chicmecoatl and her skin would be worn by a priest. It was conceived as a feminine counterpart to Centeotl and was also called Xilonen (a "hairy", which refers to the hair on unshucked corn). She appears with as Chalchiuhtlicue. It is generally characterized by bringing ears of corn. It is presented in three different forms:

# As a young girl with flowers in her hands

# As a woman who accompany death

# As a mother with sun as a shield

Aztec God #3 - Chantico

In Mythology of Aztec, Chantico ( "she who lives in the dwelling") was the goddess of fireplace and volcanoes. She broke fasting by eating grilled fish and paprikat, and was transformed into a dog by Tonacatecuhtli. She has crown adorned with of toxic cactus barbs, and may change into a red snake.

Aztec God #2 - Chalchiuhtlicue

In Aztec mythology, Chalchiuhtlicue (also known as Chalciuhtlicue or Chalcihuitlicue) (“She skirts Jade") was the goddess of lakes and streams. It is also a patron of birth and plays a role in baptisms of Aztec community. In the five suns myth, she rule the Fourth World, which was obliterated in a big flood. Her spouse was Tlaloc and with it, she gave birth to Tecciztecatl. In its aquatic aspect, it was called Acuecucyoticihuati, goddess of the sea, streams and other water and the patroness of women in the workforce. She also was said to the spouse of Xiuhtecuhtli. It is sometimes associated with a goddess of rain, Matlalcueitl.

Chalciuhtlicue was shown wearing a green short skirt and with black streaks on the her face. In some scenes infants be seen in a jet of water that is come out from her skirts. Sometimes it is symbolized by a stream with a pear tree on a riverside.

Langganan:

Komentar (Atom)